Artificial intelligence is the next industrial revolution. Its proliferation and gradual improvement will profoundly change our economy and daily lives. However, as AI tools become more powerful and efficient, their potential negative impacts raise concerns among institutions and the need to regulate them.

The European Union has established itself as a pioneer in governing this new field. On March 13, 2024, the European Parliament approved the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), which lays the foundations for regulating the use of AI in the EU. It is the first legal framework for the development and deployment of AI technology.

The AI Act serves two purposes: providing legal certainty to facilitate investment and innovation while ensuring the safety and trustworthiness of AI systems and protecting fundamental rights. It recognises AI’s fast evolution and takes a future-proof approach to adapt rules to technological innovation.

The regulation intends AI as a “machine-based system designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy, and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environment”. This definition is purposely broad and covers popular AI-generative systems like ChatGPT.

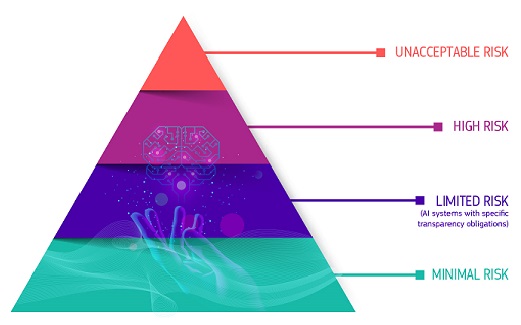

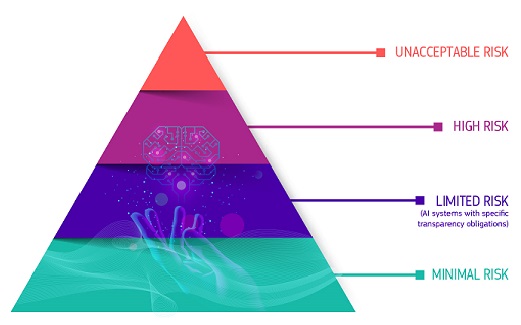

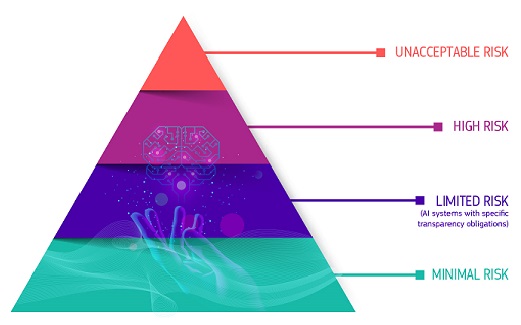

The AI Act employs a risk-based approach and categorises AI into four risk levels. The first category is “unacceptable risk,” which includes AI systems that pose a significant threat to people and will be banned. These include emotion recognition systems, such as social scoring that rates people’s behaviour or predictive policing that uses data to anticipate criminal activity, as well as biometric categorisation and categorisation of individuals that use sensitive information such as race, sexual orientation, political opinions, or religion. Additionally, untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage to create facial recognition databases is prohibited, except for law enforcement.

The second category is “high risk,” which covers AI systems that have the potential to harm health, safety, fundamental rights, democracy, and the rule of law. These systems are permitted but are closely monitored. Examples include critical infrastructure, education, employment, healthcare, banking, and specific law enforcement, justice, and border control systems.

The third category is “limited risk,” which pertains to “general-purpose” AI systems, including generative AI that produces texts, images, and videos that look remarkably real. These systems are not transparent, and the AI Act introduces transparency requirements for them. All systems in this category must comply with EU copyright laws and provide detailed summaries of the content used for training. Models that can simulate human-like intelligence and pose a systemic risk must undergo model evaluations, report severe incidents, and conduct “adversarial testing” to test the model’s safeguards. This category also includes “deepfakes,” AI-generated images, videos, or audio recordings manipulated to look genuine. The AI Act mandates that companies, public bodies, and individuals clearly label whether their content has been artificially generated or manipulated. Lastly, “minimal risk” AI includes free-to-use AI systems, such as AI-enabled video games or spam filters.

The regulation applies to all AI systems that access the EU market and is expected to come into force at the end of May after the formal endorsement by the Council of the European Union. It will be fully applicable only after two years since many aspects will require 12 to 24 months to implement, except for “unacceptable risks” systems, which will enter into force within six months from the approval of the text. The newly established European AI Office within the Commission will oversee the whole process.

However, there are still doubts about its effectiveness. The Act has caused controversy among politicians, companies and civil society. While some tech companies like Amazon support the regulation, others like Meta believe it could hinder innovation and competition. Meanwhile, some human rights groups have raised concerns about the lack of adequate privacy and human rights protection. They have highlighted the dangers of high-risk AI systems that may interfere with fundamental rights, and they ask for stronger measures to prevent discrimination. Using untargeted facial recognition and emotion recognition technologies in public places is considered an “unacceptable risk” and will be prohibited except for law enforcement purposes. However, this exception for national security could be misused, leading to potential risks, especially for vulnerable groups. AI providers may also bypass the requirements, so their system does not classify as high-risk.

The EU struggles to balance technological innovation and the need to protect against potential harm. The efforts to develop “trustworthy AI” may oversimplify the complex issue of trust and risk acceptability. Future challenges include effective enforcement, oversight and control, procedural rights and remedy mechanisms, institutional ambiguities and consideration of sustainability issues. The AI Act should protect fundamental rights and strengthen democratic accountability and judicial oversight.

At EAVI, we think that while opportunities should be considered, AI policies should prioritise people’s interests. Therefore, media literacy skills are also essential for managing AI technologies.

–

References:

European Parliament. (2024, March 13). Artificial Intelligence Act: MEPs adopt landmark law.

Lissens, S. (2024, March 11). The new EU Artificial Intelligence Act: pioneering or imposing?

Artificial intelligence is the next industrial revolution. Its proliferation and gradual improvement will profoundly change our economy and daily lives. However, as AI tools become more powerful and efficient, their potential negative impacts raise concerns among institutions and the need to regulate them.

The European Union has established itself as a pioneer in governing this new field. On March 13, 2024, the European Parliament approved the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), which lays the foundations for regulating the use of AI in the EU. It is the first legal framework for the development and deployment of AI technology.

The AI Act serves two purposes: providing legal certainty to facilitate investment and innovation while ensuring the safety and trustworthiness of AI systems and protecting fundamental rights. It recognises AI’s fast evolution and takes a future-proof approach to adapt rules to technological innovation.

The regulation intends AI as a “machine-based system designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy, and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environment”. This definition is purposely broad and covers popular AI-generative systems like ChatGPT.

The AI Act employs a risk-based approach and categorises AI into four risk levels. The first category is “unacceptable risk,” which includes AI systems that pose a significant threat to people and will be banned. These include emotion recognition systems, such as social scoring that rates people’s behaviour or predictive policing that uses data to anticipate criminal activity, as well as biometric categorisation and categorisation of individuals that use sensitive information such as race, sexual orientation, political opinions, or religion. Additionally, untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage to create facial recognition databases is prohibited, except for law enforcement.

The second category is “high risk,” which covers AI systems that have the potential to harm health, safety, fundamental rights, democracy, and the rule of law. These systems are permitted but are closely monitored. Examples include critical infrastructure, education, employment, healthcare, banking, and specific law enforcement, justice, and border control systems.

The third category is “limited risk,” which pertains to “general-purpose” AI systems, including generative AI that produces texts, images, and videos that look remarkably real. These systems are not transparent, and the AI Act introduces transparency requirements for them. All systems in this category must comply with EU copyright laws and provide detailed summaries of the content used for training. Models that can simulate human-like intelligence and pose a systemic risk must undergo model evaluations, report severe incidents, and conduct “adversarial testing” to test the model’s safeguards. This category also includes “deepfakes,” AI-generated images, videos, or audio recordings manipulated to look genuine. The AI Act mandates that companies, public bodies, and individuals clearly label whether their content has been artificially generated or manipulated. Lastly, “minimal risk” AI includes free-to-use AI systems, such as AI-enabled video games or spam filters.

The regulation applies to all AI systems that access the EU market and is expected to come into force at the end of May after the formal endorsement by the Council of the European Union. It will be fully applicable only after two years since many aspects will require 12 to 24 months to implement, except for “unacceptable risks” systems, which will enter into force within six months from the approval of the text. The newly established European AI Office within the Commission will oversee the whole process.

However, there are still doubts about its effectiveness. The Act has caused controversy among politicians, companies and civil society. While some tech companies like Amazon support the regulation, others like Meta believe it could hinder innovation and competition. Meanwhile, some human rights groups have raised concerns about the lack of adequate privacy and human rights protection. They have highlighted the dangers of high-risk AI systems that may interfere with fundamental rights, and they ask for stronger measures to prevent discrimination. Using untargeted facial recognition and emotion recognition technologies in public places is considered an “unacceptable risk” and will be prohibited except for law enforcement purposes. However, this exception for national security could be misused, leading to potential risks, especially for vulnerable groups. AI providers may also bypass the requirements, so their system does not classify as high-risk.

The EU struggles to balance technological innovation and the need to protect against potential harm. The efforts to develop “trustworthy AI” may oversimplify the complex issue of trust and risk acceptability. Future challenges include effective enforcement, oversight and control, procedural rights and remedy mechanisms, institutional ambiguities and consideration of sustainability issues. The AI Act should protect fundamental rights and strengthen democratic accountability and judicial oversight.

At EAVI, we think that while opportunities should be considered, AI policies should prioritise people’s interests. Therefore, media literacy skills are also essential for managing AI technologies.

–

References:

European Parliament. (2024, March 13). Artificial Intelligence Act: MEPs adopt landmark law.

Lissens, S. (2024, March 11). The new EU Artificial Intelligence Act: pioneering or imposing?

Artificial intelligence is the next industrial revolution. Its proliferation and gradual improvement will profoundly change our economy and daily lives. However, as AI tools become more powerful and efficient, their potential negative impacts raise concerns among institutions and the need to regulate them.

The European Union has established itself as a pioneer in governing this new field. On March 13, 2024, the European Parliament approved the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), which lays the foundations for regulating the use of AI in the EU. It is the first legal framework for the development and deployment of AI technology.

The AI Act serves two purposes: providing legal certainty to facilitate investment and innovation while ensuring the safety and trustworthiness of AI systems and protecting fundamental rights. It recognises AI’s fast evolution and takes a future-proof approach to adapt rules to technological innovation.

The regulation intends AI as a “machine-based system designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy, and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environment”. This definition is purposely broad and covers popular AI-generative systems like ChatGPT.

The AI Act employs a risk-based approach and categorises AI into four risk levels. The first category is “unacceptable risk,” which includes AI systems that pose a significant threat to people and will be banned. These include emotion recognition systems, such as social scoring that rates people’s behaviour or predictive policing that uses data to anticipate criminal activity, as well as biometric categorisation and categorisation of individuals that use sensitive information such as race, sexual orientation, political opinions, or religion. Additionally, untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage to create facial recognition databases is prohibited, except for law enforcement.

The second category is “high risk,” which covers AI systems that have the potential to harm health, safety, fundamental rights, democracy, and the rule of law. These systems are permitted but are closely monitored. Examples include critical infrastructure, education, employment, healthcare, banking, and specific law enforcement, justice, and border control systems.

The third category is “limited risk,” which pertains to “general-purpose” AI systems, including generative AI that produces texts, images, and videos that look remarkably real. These systems are not transparent, and the AI Act introduces transparency requirements for them. All systems in this category must comply with EU copyright laws and provide detailed summaries of the content used for training. Models that can simulate human-like intelligence and pose a systemic risk must undergo model evaluations, report severe incidents, and conduct “adversarial testing” to test the model’s safeguards. This category also includes “deepfakes,” AI-generated images, videos, or audio recordings manipulated to look genuine. The AI Act mandates that companies, public bodies, and individuals clearly label whether their content has been artificially generated or manipulated. Lastly, “minimal risk” AI includes free-to-use AI systems, such as AI-enabled video games or spam filters.

The regulation applies to all AI systems that access the EU market and is expected to come into force at the end of May after the formal endorsement by the Council of the European Union. It will be fully applicable only after two years since many aspects will require 12 to 24 months to implement, except for “unacceptable risks” systems, which will enter into force within six months from the approval of the text. The newly established European AI Office within the Commission will oversee the whole process.

However, there are still doubts about its effectiveness. The Act has caused controversy among politicians, companies and civil society. While some tech companies like Amazon support the regulation, others like Meta believe it could hinder innovation and competition. Meanwhile, some human rights groups have raised concerns about the lack of adequate privacy and human rights protection. They have highlighted the dangers of high-risk AI systems that may interfere with fundamental rights, and they ask for stronger measures to prevent discrimination. Using untargeted facial recognition and emotion recognition technologies in public places is considered an “unacceptable risk” and will be prohibited except for law enforcement purposes. However, this exception for national security could be misused, leading to potential risks, especially for vulnerable groups. AI providers may also bypass the requirements, so their system does not classify as high-risk.

The EU struggles to balance technological innovation and the need to protect against potential harm. The efforts to develop “trustworthy AI” may oversimplify the complex issue of trust and risk acceptability. Future challenges include effective enforcement, oversight and control, procedural rights and remedy mechanisms, institutional ambiguities and consideration of sustainability issues. The AI Act should protect fundamental rights and strengthen democratic accountability and judicial oversight.

At EAVI, we think that while opportunities should be considered, AI policies should prioritise people’s interests. Therefore, media literacy skills are also essential for managing AI technologies.

–

References:

European Parliament. (2024, March 13). Artificial Intelligence Act: MEPs adopt landmark law.

Lissens, S. (2024, March 11). The new EU Artificial Intelligence Act: pioneering or imposing?