Conclusions drawn from the discussion with Stacey Featherstone and Athina Karatzogianni – 7th of December (EAVI Conversations 2021)

Conversations on digital citizenship are never predictable, as citizens’ rights and duties are many and the variables influencing their direct participation are countless. For the session with Prof. Athina Kataztogianni (Prof of Media and Communication at the University of Leicester) and Stacey Featherstone (Public Policy Manager at Meta), the focus has been the use of social media to foster digital citizenship and social movements.

Digital citizenship shifted from being just about digital skills, to encompass also digital well-being and mental health. Meta is promoting digital citizenship through a holistic approach, fostering online communities, and allowing people to participate in public life in a way that is meaningful to them (mobilising around important causes, running their business, accessing information, etc.). While Meta offers the space where all of this can happen, it is also important for citizens to build resilience on their side and learn how to defend themselves from internet risks. Within the scholarship, another important component is the digital environment, as it is the only space where digital citizens claim human and civil rights and where they behave and act to make these claims.

The perception of digital citizenship has evolved together with technological development. In the first decade of the 21st century, there was a widespread faith in technology and thanks to the web’s democratic design, it was believed it could have had a democratizing effect on societies, fostering political change (especially in the Arab Spring’s aftermath). This ideology was called technological utopianism, which pictured the web as a liberation technology.[1] Basically, by enhancing participation through ICTs, a society might generate innovation and social change. On the other hand, since 2016, criticism of this blind faith started arising, mainly due to the US elections and the Brexit referendum. All our activities are taking place online, generating location data and metadata, which are collected, stored, monitored, and shared. These could be easily sold by social media services to data brokers, intelligence agencies, public administrations, etc. This cast a worrying side to the ability of citizens to genuinely express themselves online participating freely in a non-manipulated public life.

Because of the above-mentioned threats, the link between democracy and the right use of online platforms became stronger, bringing social media companies to intervene, safeguarding transparency and safety online. Meta, for instance, is active in the area of digital citizenship, but eradicating all the root problems influencing democracy nowadays is not an easy job. Their action plan is twofold: on one side Meta develops technological responses, relying on product features and tools, constantly improving, and updating the actual platform; on the other side on programmatic responses, operating through partnerships, collaborations, and campaigns. Since there is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to democracy and elections, the company collaborates with local umbrella organisations that own the right channels and know the right approaches to localise the actions. Despite having global community standards in the domain of digital citizenship, Meta also has declination policies in different countries resulting from global programming.

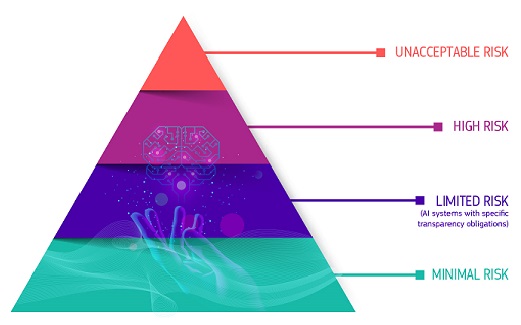

According to Prof. Karatzogianni, it took a long time to understand that what happens online has consequences in the real world, politically, socially, and economically; therefore, responses and solutions have been slow and ineffective up until now. Generally, there has been criticism towards social media platforms, especially Facebook (now Meta), due to content moderation. Overreliance on AI and algorithms caused several problems especially at the micro-level (reporting and cancelling accounts that turned out not to be fake), so AI is not a solution, as it is unable to analyse all the nuances in online discourse. It seems clear that there should be more collaboration between different actors on this topic, as companies and governments alone cannot take on them the exclusive burden of making the digital space more accountable.

We haven’t yet analysed the component of civic participation in the form of social movements. In less developed countries people tend to protest on the streets, while in more developed countries people rely more on the use of platforms like Tik-Tok, WhatsApp, etc. to get organised. While 10 years ago there was a sort of scepticism on the use of social media for activism (as private companies are making profit out of them), nowadays all sorts of movements, even the right and left extremist ones, are using them, because the public square is on the internet. It is possible, therefore, to talk about digital activism. With the pandemic, the internet and social media definitely became the core of mobilisation, rather than just tools for communication.

Based on the DigiGen research[2], it is clear though that social movements don’t use social media in the same way all around Europe. As it happened with the concept of digital citizenship, also the use of social media has changed over time when adopted by social movements. The research shows that, especially in the UK, the Extinction Rebellion brought innovation in terms of communication and organisation. The rebellion didn’t rely on traditional social media, but it used more secured platforms (Telegram, Signal, Glassfrog, Mattermost), and the decision making happened by consent. It is also true that the pandemic helped them to restructure through intergenerational mentoring. The level of distrust was different in the countries part of the sample: it was really high in Greece (both towards the government and social media operations), while it was not preoccupying in Estonia.[3]

Based on the poll submitted to the participants, 65% of them hadn’t been active or participated in any social movement in the last year. The analysis on the platforms owned by Meta shows that even if people are not actually participating in movements, they are anyway following their actions online. Predominant are conversations about climate change.

The pandemic was a trial crisis for Meta, and thanks to the lessons learnt from it, Meta decided to apply them to their climate change campaigns since, at the end of the day, climate change is another global crisis as COVID-19. Meta does intervene in the debate on climate change and has established a Climate Science Information Centre, where users can access reliable information on the topic, cooperate with UNFCC, taking action especially on climate misinformation

Our speakers hope that in the future more and more people will actively participate online and that more research will be done to discover the impact of digitalisation on climate change!

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technological_utopianism#History

[2] https://www.digigen.eu/results/online-political-behaviour-and-ideological-production-by-young-people/

[3] The research took place in Estonia, Greece and UK.

Are you interested in watching the different sessions of the EAVI Conversations 2021?

Conclusions drawn from the discussion with Stacey Featherstone and Athina Karatzogianni – 7th of December (EAVI Conversations 2021)

Conversations on digital citizenship are never predictable, as citizens’ rights and duties are many and the variables influencing their direct participation are countless. For the session with Prof. Athina Kataztogianni (Prof of Media and Communication at the University of Leicester) and Stacey Featherstone (Public Policy Manager at Meta), the focus has been the use of social media to foster digital citizenship and social movements.

Digital citizenship shifted from being just about digital skills, to encompass also digital well-being and mental health. Meta is promoting digital citizenship through a holistic approach, fostering online communities, and allowing people to participate in public life in a way that is meaningful to them (mobilising around important causes, running their business, accessing information, etc.). While Meta offers the space where all of this can happen, it is also important for citizens to build resilience on their side and learn how to defend themselves from internet risks. Within the scholarship, another important component is the digital environment, as it is the only space where digital citizens claim human and civil rights and where they behave and act to make these claims.

The perception of digital citizenship has evolved together with technological development. In the first decade of the 21st century, there was a widespread faith in technology and thanks to the web’s democratic design, it was believed it could have had a democratizing effect on societies, fostering political change (especially in the Arab Spring’s aftermath). This ideology was called technological utopianism, which pictured the web as a liberation technology.[1] Basically, by enhancing participation through ICTs, a society might generate innovation and social change. On the other hand, since 2016, criticism of this blind faith started arising, mainly due to the US elections and the Brexit referendum. All our activities are taking place online, generating location data and metadata, which are collected, stored, monitored, and shared. These could be easily sold by social media services to data brokers, intelligence agencies, public administrations, etc. This cast a worrying side to the ability of citizens to genuinely express themselves online participating freely in a non-manipulated public life.

Because of the above-mentioned threats, the link between democracy and the right use of online platforms became stronger, bringing social media companies to intervene, safeguarding transparency and safety online. Meta, for instance, is active in the area of digital citizenship, but eradicating all the root problems influencing democracy nowadays is not an easy job. Their action plan is twofold: on one side Meta develops technological responses, relying on product features and tools, constantly improving, and updating the actual platform; on the other side on programmatic responses, operating through partnerships, collaborations, and campaigns. Since there is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to democracy and elections, the company collaborates with local umbrella organisations that own the right channels and know the right approaches to localise the actions. Despite having global community standards in the domain of digital citizenship, Meta also has declination policies in different countries resulting from global programming.

According to Prof. Karatzogianni, it took a long time to understand that what happens online has consequences in the real world, politically, socially, and economically; therefore, responses and solutions have been slow and ineffective up until now. Generally, there has been criticism towards social media platforms, especially Facebook (now Meta), due to content moderation. Overreliance on AI and algorithms caused several problems especially at the micro-level (reporting and cancelling accounts that turned out not to be fake), so AI is not a solution, as it is unable to analyse all the nuances in online discourse. It seems clear that there should be more collaboration between different actors on this topic, as companies and governments alone cannot take on them the exclusive burden of making the digital space more accountable.

We haven’t yet analysed the component of civic participation in the form of social movements. In less developed countries people tend to protest on the streets, while in more developed countries people rely more on the use of platforms like Tik-Tok, WhatsApp, etc. to get organised. While 10 years ago there was a sort of scepticism on the use of social media for activism (as private companies are making profit out of them), nowadays all sorts of movements, even the right and left extremist ones, are using them, because the public square is on the internet. It is possible, therefore, to talk about digital activism. With the pandemic, the internet and social media definitely became the core of mobilisation, rather than just tools for communication.

Based on the DigiGen research[2], it is clear though that social movements don’t use social media in the same way all around Europe. As it happened with the concept of digital citizenship, also the use of social media has changed over time when adopted by social movements. The research shows that, especially in the UK, the Extinction Rebellion brought innovation in terms of communication and organisation. The rebellion didn’t rely on traditional social media, but it used more secured platforms (Telegram, Signal, Glassfrog, Mattermost), and the decision making happened by consent. It is also true that the pandemic helped them to restructure through intergenerational mentoring. The level of distrust was different in the countries part of the sample: it was really high in Greece (both towards the government and social media operations), while it was not preoccupying in Estonia.[3]

Based on the poll submitted to the participants, 65% of them hadn’t been active or participated in any social movement in the last year. The analysis on the platforms owned by Meta shows that even if people are not actually participating in movements, they are anyway following their actions online. Predominant are conversations about climate change.

The pandemic was a trial crisis for Meta, and thanks to the lessons learnt from it, Meta decided to apply them to their climate change campaigns since, at the end of the day, climate change is another global crisis as COVID-19. Meta does intervene in the debate on climate change and has established a Climate Science Information Centre, where users can access reliable information on the topic, cooperate with UNFCC, taking action especially on climate misinformation

Our speakers hope that in the future more and more people will actively participate online and that more research will be done to discover the impact of digitalisation on climate change!

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technological_utopianism#History

[2] https://www.digigen.eu/results/online-political-behaviour-and-ideological-production-by-young-people/

[3] The research took place in Estonia, Greece and UK.

Are you interested in watching the different sessions of the EAVI Conversations 2021?

Conclusions drawn from the discussion with Stacey Featherstone and Athina Karatzogianni – 7th of December (EAVI Conversations 2021)

Conversations on digital citizenship are never predictable, as citizens’ rights and duties are many and the variables influencing their direct participation are countless. For the session with Prof. Athina Kataztogianni (Prof of Media and Communication at the University of Leicester) and Stacey Featherstone (Public Policy Manager at Meta), the focus has been the use of social media to foster digital citizenship and social movements.

Digital citizenship shifted from being just about digital skills, to encompass also digital well-being and mental health. Meta is promoting digital citizenship through a holistic approach, fostering online communities, and allowing people to participate in public life in a way that is meaningful to them (mobilising around important causes, running their business, accessing information, etc.). While Meta offers the space where all of this can happen, it is also important for citizens to build resilience on their side and learn how to defend themselves from internet risks. Within the scholarship, another important component is the digital environment, as it is the only space where digital citizens claim human and civil rights and where they behave and act to make these claims.

The perception of digital citizenship has evolved together with technological development. In the first decade of the 21st century, there was a widespread faith in technology and thanks to the web’s democratic design, it was believed it could have had a democratizing effect on societies, fostering political change (especially in the Arab Spring’s aftermath). This ideology was called technological utopianism, which pictured the web as a liberation technology.[1] Basically, by enhancing participation through ICTs, a society might generate innovation and social change. On the other hand, since 2016, criticism of this blind faith started arising, mainly due to the US elections and the Brexit referendum. All our activities are taking place online, generating location data and metadata, which are collected, stored, monitored, and shared. These could be easily sold by social media services to data brokers, intelligence agencies, public administrations, etc. This cast a worrying side to the ability of citizens to genuinely express themselves online participating freely in a non-manipulated public life.

Because of the above-mentioned threats, the link between democracy and the right use of online platforms became stronger, bringing social media companies to intervene, safeguarding transparency and safety online. Meta, for instance, is active in the area of digital citizenship, but eradicating all the root problems influencing democracy nowadays is not an easy job. Their action plan is twofold: on one side Meta develops technological responses, relying on product features and tools, constantly improving, and updating the actual platform; on the other side on programmatic responses, operating through partnerships, collaborations, and campaigns. Since there is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to democracy and elections, the company collaborates with local umbrella organisations that own the right channels and know the right approaches to localise the actions. Despite having global community standards in the domain of digital citizenship, Meta also has declination policies in different countries resulting from global programming.

According to Prof. Karatzogianni, it took a long time to understand that what happens online has consequences in the real world, politically, socially, and economically; therefore, responses and solutions have been slow and ineffective up until now. Generally, there has been criticism towards social media platforms, especially Facebook (now Meta), due to content moderation. Overreliance on AI and algorithms caused several problems especially at the micro-level (reporting and cancelling accounts that turned out not to be fake), so AI is not a solution, as it is unable to analyse all the nuances in online discourse. It seems clear that there should be more collaboration between different actors on this topic, as companies and governments alone cannot take on them the exclusive burden of making the digital space more accountable.

We haven’t yet analysed the component of civic participation in the form of social movements. In less developed countries people tend to protest on the streets, while in more developed countries people rely more on the use of platforms like Tik-Tok, WhatsApp, etc. to get organised. While 10 years ago there was a sort of scepticism on the use of social media for activism (as private companies are making profit out of them), nowadays all sorts of movements, even the right and left extremist ones, are using them, because the public square is on the internet. It is possible, therefore, to talk about digital activism. With the pandemic, the internet and social media definitely became the core of mobilisation, rather than just tools for communication.

Based on the DigiGen research[2], it is clear though that social movements don’t use social media in the same way all around Europe. As it happened with the concept of digital citizenship, also the use of social media has changed over time when adopted by social movements. The research shows that, especially in the UK, the Extinction Rebellion brought innovation in terms of communication and organisation. The rebellion didn’t rely on traditional social media, but it used more secured platforms (Telegram, Signal, Glassfrog, Mattermost), and the decision making happened by consent. It is also true that the pandemic helped them to restructure through intergenerational mentoring. The level of distrust was different in the countries part of the sample: it was really high in Greece (both towards the government and social media operations), while it was not preoccupying in Estonia.[3]

Based on the poll submitted to the participants, 65% of them hadn’t been active or participated in any social movement in the last year. The analysis on the platforms owned by Meta shows that even if people are not actually participating in movements, they are anyway following their actions online. Predominant are conversations about climate change.

The pandemic was a trial crisis for Meta, and thanks to the lessons learnt from it, Meta decided to apply them to their climate change campaigns since, at the end of the day, climate change is another global crisis as COVID-19. Meta does intervene in the debate on climate change and has established a Climate Science Information Centre, where users can access reliable information on the topic, cooperate with UNFCC, taking action especially on climate misinformation

Our speakers hope that in the future more and more people will actively participate online and that more research will be done to discover the impact of digitalisation on climate change!

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technological_utopianism#History

[2] https://www.digigen.eu/results/online-political-behaviour-and-ideological-production-by-young-people/

[3] The research took place in Estonia, Greece and UK.