In view of the elections that will be held in 2024 in the EU and other parts of the world including the US and UK, there are various challenges to democratic processes as technological advancements are on the rise. It is argued that electoral periods and times of political crisis serve as fertile ground for the production and dissemination of AI-generated content, heightening concerns about the impact on public perception and democratic processes. Recent instances have demonstrated the alarming potential of AI to enable the production of deceptive narratives, with such disinformation finding its way into the public sphere via the internet and social media channels. In this regard, disinformation is defined as “false information with intent to mislead”. Therefore, improved efforts in media literacy are crucial.

In her article “How AI Changes the Way Disinformation is Produced, Disseminated, and Can Be Countered”, Katarina Kertysova identifies various threats associated with AI techniques in the political area including user profiling, micro-targeting and deep fakes. User profiling and micro-targeting refer to the process of determining individuals’ beliefs, needs, traits and vulnerabilities, and then targeting those who are most susceptible to influence with highly-personalised content. Furthermore, personalized targeting can be combined with Natural Language Generation tools to produce content for diverse users automatically. Election outcomes could be negatively impacted by the spread of disinformation with intensive automated methods right before the election silence during which political campaigning is halted. In this case, personal data is used for the objective of profiling and targeting with political messages which breaches the existing EU data protection principles.

“Deep fakes” refer to digitally altered audio or visual content that is extremely realistic and virtually identical to the original content. This way of applying AI to audio and video content production is now being used in the online areas of politics and international affairs. It is expected that producing such biased materials is going to be easy and common soon. The AI-generated content that depicts individuals saying and doing things they did not say or do has the potential to undermine leaders and individuals, and probably impact the election outcomes. For instance, an illustration of deep fakes emerged in the form of an AI-manipulated image portraying an elderly man being assaulted by the police in France. This image circulated online amidst the widespread protests that took place in March 2023.

This threat is also demonstrated in the case of Slovakia’s elections held in September 2023. A few days before the election, an audio recording surfaced on Facebook featuring purported voices of Michal Šimečka, leader of the Progressive Slovakia party, and Monika Tódová from Denník N newspaper. The conversation allegedly discussed election rigging, including buying votes from the marginalized Roma minority. While Šimečka and Denník N swiftly denounced the audio as fake, fact-checkers identified signs of AI manipulation, making debunking difficult within the 48-hour pre-election media silence. The election, a close race between Progressive Slovakia and SMER, resulted in the latter’s victory. The incident raised concerns about the susceptibility of European elections to AI-driven disinformation, with Slovakia serving as a demonstrable case. Furthermore, fact-checkers such as Demagog, a Meta partner, faced challenges in combating AI-generated content, especially audio deep fakes.

Slovakia’s election took place after the introduction of the EU’s Digital Services Act, aiming to enhance online human rights protection. The act required platforms to be more proactive and transparent in moderating disinformation. However, the effectiveness of these measures remains a subject of scrutiny, as disinformation, including AI-generated deep fakes, persisted during the election. This case highlights the importance of media literacy also in the context of election periods. As technological advancements, particularly in AI, make it increasingly difficult to discern between authentic and manipulated content, individuals should be equipped with the necessary skills to critically evaluate information and to avoid being a target of disinformation activities.

Accordingly, Kertysova argues that technological solutions are not enough to tackle the challenge of disinformation during elections. Solutions for the disinformation should rely on the psychological aspect in addition to the technical. Therefore, one of the most efficient and powerful strategies to reestablish a positive connection with information and strengthen democracies’ resilience is to improve media and digital literacy.

According to a survey conducted by Luminate in September, 57% of French citizens and 71% of German citizens are worried about the potential risks that deep fake and artificial intelligence technologies pose to elections. Furthermore, 81% of French citizens and 75% of German citizens think that their right to oppose social media companies using their personal data for advertisement is important. Despite this fact, as demonstrated by the case of Slovakia’s elections, there is still a persistent risk of disinformation fueled by AI-generated content. Even with increased public awareness, AI-generated disinformation continues to pose challenges to democracy, especially considering the continuous developments in AI technology.

Therefore, improving the public’s ability to navigate and discern information is crucial in ensuring that citizens can make informed choices considering the challenges to the democratic process posed by AI-driven disinformation. By fostering media literacy and promoting critical thinking skills, we can collectively build a defence against the influence of disinformation on the elections.

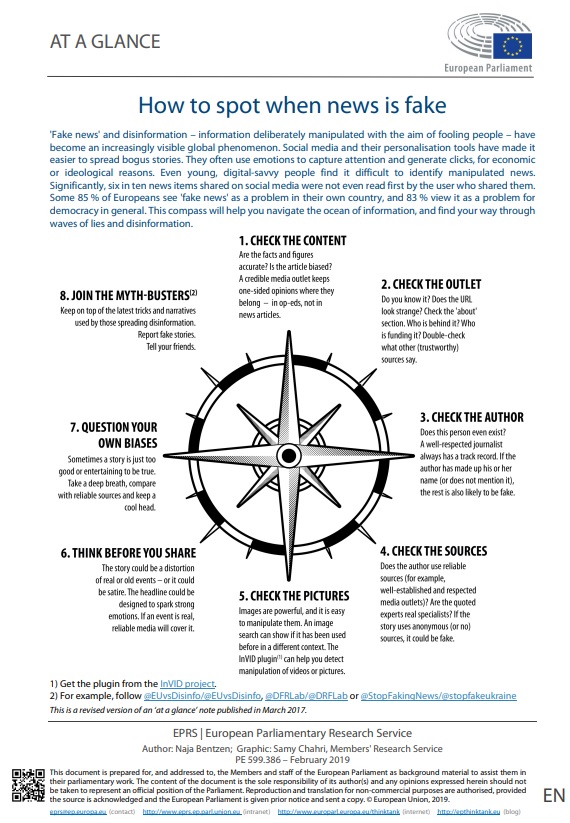

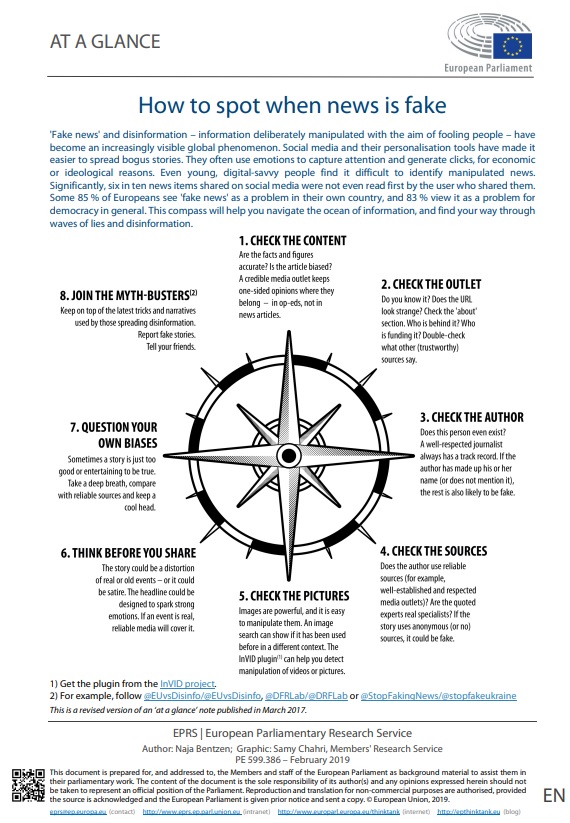

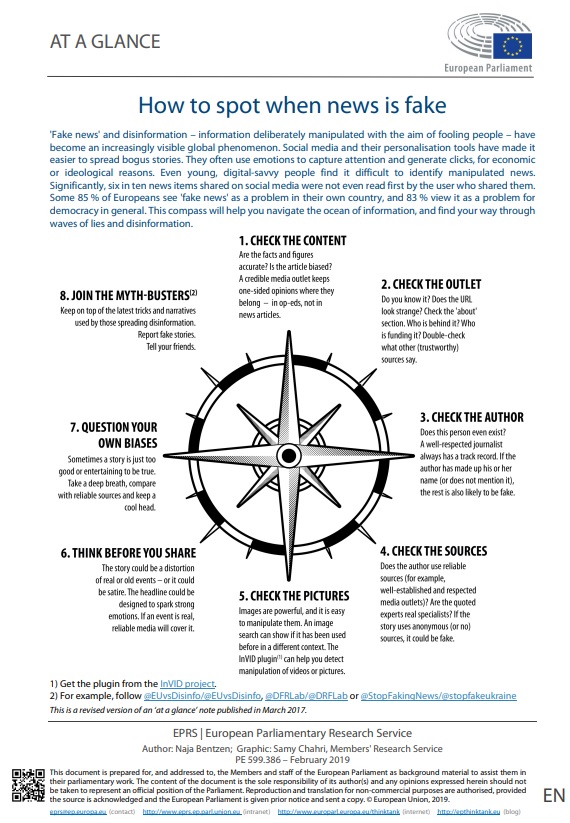

The following graphic shared by the European Parliament can also be useful to identify and recognise fake news:

In view of the elections that will be held in 2024 in the EU and other parts of the world including the US and UK, there are various challenges to democratic processes as technological advancements are on the rise. It is argued that electoral periods and times of political crisis serve as fertile ground for the production and dissemination of AI-generated content, heightening concerns about the impact on public perception and democratic processes. Recent instances have demonstrated the alarming potential of AI to enable the production of deceptive narratives, with such disinformation finding its way into the public sphere via the internet and social media channels. In this regard, disinformation is defined as “false information with intent to mislead”. Therefore, improved efforts in media literacy are crucial.

In her article “How AI Changes the Way Disinformation is Produced, Disseminated, and Can Be Countered”, Katarina Kertysova identifies various threats associated with AI techniques in the political area including user profiling, micro-targeting and deep fakes. User profiling and micro-targeting refer to the process of determining individuals’ beliefs, needs, traits and vulnerabilities, and then targeting those who are most susceptible to influence with highly-personalised content. Furthermore, personalized targeting can be combined with Natural Language Generation tools to produce content for diverse users automatically. Election outcomes could be negatively impacted by the spread of disinformation with intensive automated methods right before the election silence during which political campaigning is halted. In this case, personal data is used for the objective of profiling and targeting with political messages which breaches the existing EU data protection principles.

“Deep fakes” refer to digitally altered audio or visual content that is extremely realistic and virtually identical to the original content. This way of applying AI to audio and video content production is now being used in the online areas of politics and international affairs. It is expected that producing such biased materials is going to be easy and common soon. The AI-generated content that depicts individuals saying and doing things they did not say or do has the potential to undermine leaders and individuals, and probably impact the election outcomes. For instance, an illustration of deep fakes emerged in the form of an AI-manipulated image portraying an elderly man being assaulted by the police in France. This image circulated online amidst the widespread protests that took place in March 2023.

This threat is also demonstrated in the case of Slovakia’s elections held in September 2023. A few days before the election, an audio recording surfaced on Facebook featuring purported voices of Michal Šimečka, leader of the Progressive Slovakia party, and Monika Tódová from Denník N newspaper. The conversation allegedly discussed election rigging, including buying votes from the marginalized Roma minority. While Šimečka and Denník N swiftly denounced the audio as fake, fact-checkers identified signs of AI manipulation, making debunking difficult within the 48-hour pre-election media silence. The election, a close race between Progressive Slovakia and SMER, resulted in the latter’s victory. The incident raised concerns about the susceptibility of European elections to AI-driven disinformation, with Slovakia serving as a demonstrable case. Furthermore, fact-checkers such as Demagog, a Meta partner, faced challenges in combating AI-generated content, especially audio deep fakes.

Slovakia’s election took place after the introduction of the EU’s Digital Services Act, aiming to enhance online human rights protection. The act required platforms to be more proactive and transparent in moderating disinformation. However, the effectiveness of these measures remains a subject of scrutiny, as disinformation, including AI-generated deep fakes, persisted during the election. This case highlights the importance of media literacy also in the context of election periods. As technological advancements, particularly in AI, make it increasingly difficult to discern between authentic and manipulated content, individuals should be equipped with the necessary skills to critically evaluate information and to avoid being a target of disinformation activities.

Accordingly, Kertysova argues that technological solutions are not enough to tackle the challenge of disinformation during elections. Solutions for the disinformation should rely on the psychological aspect in addition to the technical. Therefore, one of the most efficient and powerful strategies to reestablish a positive connection with information and strengthen democracies’ resilience is to improve media and digital literacy.

According to a survey conducted by Luminate in September, 57% of French citizens and 71% of German citizens are worried about the potential risks that deep fake and artificial intelligence technologies pose to elections. Furthermore, 81% of French citizens and 75% of German citizens think that their right to oppose social media companies using their personal data for advertisement is important. Despite this fact, as demonstrated by the case of Slovakia’s elections, there is still a persistent risk of disinformation fueled by AI-generated content. Even with increased public awareness, AI-generated disinformation continues to pose challenges to democracy, especially considering the continuous developments in AI technology.

Therefore, improving the public’s ability to navigate and discern information is crucial in ensuring that citizens can make informed choices considering the challenges to the democratic process posed by AI-driven disinformation. By fostering media literacy and promoting critical thinking skills, we can collectively build a defence against the influence of disinformation on the elections.

The following graphic shared by the European Parliament can also be useful to identify and recognise fake news:

In view of the elections that will be held in 2024 in the EU and other parts of the world including the US and UK, there are various challenges to democratic processes as technological advancements are on the rise. It is argued that electoral periods and times of political crisis serve as fertile ground for the production and dissemination of AI-generated content, heightening concerns about the impact on public perception and democratic processes. Recent instances have demonstrated the alarming potential of AI to enable the production of deceptive narratives, with such disinformation finding its way into the public sphere via the internet and social media channels. In this regard, disinformation is defined as “false information with intent to mislead”. Therefore, improved efforts in media literacy are crucial.

In her article “How AI Changes the Way Disinformation is Produced, Disseminated, and Can Be Countered”, Katarina Kertysova identifies various threats associated with AI techniques in the political area including user profiling, micro-targeting and deep fakes. User profiling and micro-targeting refer to the process of determining individuals’ beliefs, needs, traits and vulnerabilities, and then targeting those who are most susceptible to influence with highly-personalised content. Furthermore, personalized targeting can be combined with Natural Language Generation tools to produce content for diverse users automatically. Election outcomes could be negatively impacted by the spread of disinformation with intensive automated methods right before the election silence during which political campaigning is halted. In this case, personal data is used for the objective of profiling and targeting with political messages which breaches the existing EU data protection principles.

“Deep fakes” refer to digitally altered audio or visual content that is extremely realistic and virtually identical to the original content. This way of applying AI to audio and video content production is now being used in the online areas of politics and international affairs. It is expected that producing such biased materials is going to be easy and common soon. The AI-generated content that depicts individuals saying and doing things they did not say or do has the potential to undermine leaders and individuals, and probably impact the election outcomes. For instance, an illustration of deep fakes emerged in the form of an AI-manipulated image portraying an elderly man being assaulted by the police in France. This image circulated online amidst the widespread protests that took place in March 2023.

This threat is also demonstrated in the case of Slovakia’s elections held in September 2023. A few days before the election, an audio recording surfaced on Facebook featuring purported voices of Michal Šimečka, leader of the Progressive Slovakia party, and Monika Tódová from Denník N newspaper. The conversation allegedly discussed election rigging, including buying votes from the marginalized Roma minority. While Šimečka and Denník N swiftly denounced the audio as fake, fact-checkers identified signs of AI manipulation, making debunking difficult within the 48-hour pre-election media silence. The election, a close race between Progressive Slovakia and SMER, resulted in the latter’s victory. The incident raised concerns about the susceptibility of European elections to AI-driven disinformation, with Slovakia serving as a demonstrable case. Furthermore, fact-checkers such as Demagog, a Meta partner, faced challenges in combating AI-generated content, especially audio deep fakes.

Slovakia’s election took place after the introduction of the EU’s Digital Services Act, aiming to enhance online human rights protection. The act required platforms to be more proactive and transparent in moderating disinformation. However, the effectiveness of these measures remains a subject of scrutiny, as disinformation, including AI-generated deep fakes, persisted during the election. This case highlights the importance of media literacy also in the context of election periods. As technological advancements, particularly in AI, make it increasingly difficult to discern between authentic and manipulated content, individuals should be equipped with the necessary skills to critically evaluate information and to avoid being a target of disinformation activities.

Accordingly, Kertysova argues that technological solutions are not enough to tackle the challenge of disinformation during elections. Solutions for the disinformation should rely on the psychological aspect in addition to the technical. Therefore, one of the most efficient and powerful strategies to reestablish a positive connection with information and strengthen democracies’ resilience is to improve media and digital literacy.

According to a survey conducted by Luminate in September, 57% of French citizens and 71% of German citizens are worried about the potential risks that deep fake and artificial intelligence technologies pose to elections. Furthermore, 81% of French citizens and 75% of German citizens think that their right to oppose social media companies using their personal data for advertisement is important. Despite this fact, as demonstrated by the case of Slovakia’s elections, there is still a persistent risk of disinformation fueled by AI-generated content. Even with increased public awareness, AI-generated disinformation continues to pose challenges to democracy, especially considering the continuous developments in AI technology.

Therefore, improving the public’s ability to navigate and discern information is crucial in ensuring that citizens can make informed choices considering the challenges to the democratic process posed by AI-driven disinformation. By fostering media literacy and promoting critical thinking skills, we can collectively build a defence against the influence of disinformation on the elections.

The following graphic shared by the European Parliament can also be useful to identify and recognise fake news: