EAVI’s secretary general Paolo Celot on EAVI’s campaign resulting in the European Parliament’s vote to re-introduce media literacy to the Audiovisual Media Services Directive.

When the European Commission opened their public consultation on the revision of the Audio Visual Media Services Directive, I had to read it twice. I could not believe that any explicit mention of media literacy was absent from its frame closed format.¹

Were I a cynic, I would have considered the absence suspect. It was almost as though the questions had been drafted in order to pre-ordain the outcome – which was that media literacy was not to feature in the Directive.

My suspicions turned out to be well-founded. When the European Commission presented its proposal in May 2016, media literacy was not mentioned even once.

I couldn’t believe it was possible. We at EAVI have worked with the European Commission for more than a decade. The importance of media literacy was highlighted for years in innumerable studies and policy documents as a critical issue when informing, inter alia, audiovisual policies.

I began to think that it was a dream, when I heard European Commissioner Tibor Navracsics saying, “I can not think of anything better than media literacy”.2

In hindsight, the signals were clear. The Commission had been quietly warping the definition of media literacy to mean the acquisition of technical skills alone. The Europe2020 strategy, for instance, asserted that citizens would need to grasp media literacy skills to advantage them in the labour market. These technical competencies, what we call digital skills, bring with them easily identifiable commercial benefits for certain industries: this is to be expected, the European Union promotes the Single Market and the elimination of trade barriers.

But that cannot justify the redefinition of media literacy as simply the promotion of online access, shedding the critical aptitudes of being able to evaluate and assess media messages. To do so is to ignore its preeminent social, cultural and political value (in addition to its obvious technical and economic implications).

In our opinion, the Commission’s approach, to disregard any reference to research-based evidence, ran counter to the spirit of the Directive itself.

The actions of the Commission in this matter were justified by claiming that media literacy is a matter of education alone, which would, by happy coincidence, render it the responsibility of national governments. But for the Commission to wash its hands of the matter was to overlook the fact that the competencies associated with media literacy impact upon content access, consumer protection, access and right to information, recognition of media pluralism, and many more. It was the reason that media literacy provisions were included in the Directive in the first instance.

EAVI accepts that it is not the only voice in this conversation. Other groups who petition and lobby the Commission on the matter of media literacy include the media industry itself, who doubtless benefit from consumer base with the technical competency to access the media, but not the critical faculty to demand quality, ethical media content. Could it really be that their power and resources would ensure that the definition of media literacy in the Directive did not inconvenience them?

We at EAVI fought back. As part of the research community3, we argued for years that technology is certainly capable of enriching the lives of citizens, but those competencies should not focus exclusively on technical skills. Media literacy is, in fact, the development of individual critical understanding and citizens’ participation in public life. It is, quite simply, the empowerment and interaction of individuals through the media.

EAVI’s campaign was relentless: we drafted position papers and lobbied MEPs and Committee Members. In June 2016, we organised a debate at the European Parliament, where the next decision on the Directive was to be taken.

The peak of the campaign was the proposal to amend the Directive, which was drafted with the help of many colleagues4, and submitted to Members of the European Parliament in October 2016.

Following from this, some MEPs from across the political spectrum, including the Rapporteur of the AVMSD and the Chairman of the Culture Committee, put forward our amendments. On 25 April 2017, and as a result of our long and tireless campaign, measures to reintroduce media literacy in the AVMSD, in its true form, were adopted by the European Parliament Culture Committee.5

I am glad as ever to observe that the EU legislative process allowed us finally to influence positively the dossier in question. Although EU bureaucracy is often slow, it does give us a real chance to participate, if you know how to navigate the complex environment.

The Directive now includes a comprehensive definition of media literacy. It also asks for Member States to report on practices, policies and accompanying measures they support in the field of media literacy.

Media literacy was nowhere: now it is here!

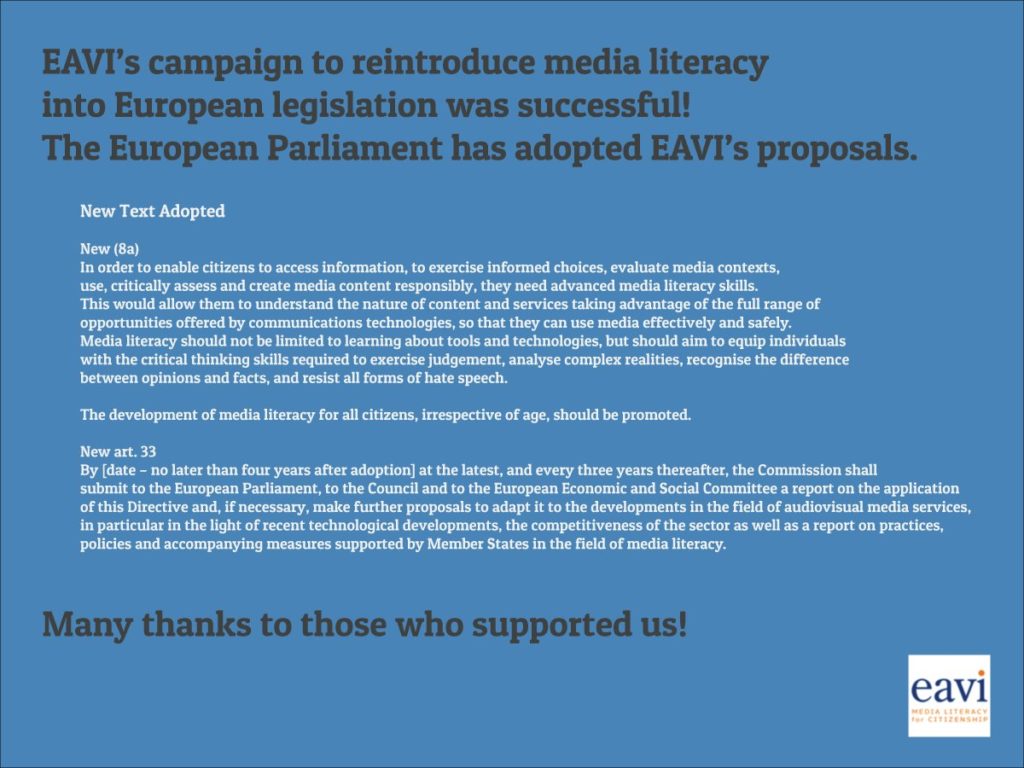

See the new text adopted by the Culture Committee of the European Parliament

New (8a)

In order to enable citizens to access information, to exercise informed choices, evaluate media contexts, use, critically assess and create media content responsibly, they need advanced media literacy skills. This would allow them to understand the nature of content and services taking advantage of the full range of opportunities offered by communications technologies, so that they can use media effectively and safely. Media literacy should not be limited to learning about tools and technologies, but should aim to equip individuals with the critical thinking skills required to exercise judgement, analyse complex realities, recognise the difference between opinions and facts, and resist all forms of hate speech. The development of media literacy for all citizens, irrespective of age, should be promoted.New art. 33

By[date – no later than four years after adoption] at the latest, and every three years thereafter, the Commission shall submit to the European Parliament, to the Council and to the European Economic and Social Committee a report on the application of this Directive and, if necessary, make further proposals to adapt it to the developments in the field of audiovisual media services, in particular in the light of recent technological developments, the competitiveness of the sector as well as a report on practices, policies and accompanying measures supported by Member States in the field of media literacy.

1. No explicit text references appeared neither among the issues listed to be considered in the review of the AVMSD nor in any subsequent question (with the marginal exception of a mention, in brackets, within the section protection of minors).

2. Difference Day event in Brussels, on 3 May 2017 see www.differenceday.com

3. European-wide studies including by UNESCO, OECD, the Council of Europe, and mainly the European Commission itself, have highlighted the significance of a critical consumption of media content.

4. Including Divina Frau Meigs of UNESCO GAPMIL, Leo Pekkala of the National Audiovisual Institute in Finland, Giovanni Melogli of the Alliance of Journalistes and Maia Cappello of the European Audiovisual Observatory who provided factual information which allowed decision makers to conclude that media literacy should be part of the Directive.

5. Amendements presented by members of the European Parliament Petra Kammerevert, Julie Ward, Silvia Costa, Curzio Maltese, Zdzislaw Krasnodebski, Isabella Adinolfi, Nikolaos Chountis, Martina Michels. The legislative process foresees more steps, and key decisions will be taken by the Plenary of the EP and the Council (the national governments).

EAVI’s secretary general Paolo Celot on EAVI’s campaign resulting in the European Parliament’s vote to re-introduce media literacy to the Audiovisual Media Services Directive.

When the European Commission opened their public consultation on the revision of the Audio Visual Media Services Directive, I had to read it twice. I could not believe that any explicit mention of media literacy was absent from its frame closed format.¹

Were I a cynic, I would have considered the absence suspect. It was almost as though the questions had been drafted in order to pre-ordain the outcome – which was that media literacy was not to feature in the Directive.

My suspicions turned out to be well-founded. When the European Commission presented its proposal in May 2016, media literacy was not mentioned even once.

I couldn’t believe it was possible. We at EAVI have worked with the European Commission for more than a decade. The importance of media literacy was highlighted for years in innumerable studies and policy documents as a critical issue when informing, inter alia, audiovisual policies.

I began to think that it was a dream, when I heard European Commissioner Tibor Navracsics saying, “I can not think of anything better than media literacy”.2

In hindsight, the signals were clear. The Commission had been quietly warping the definition of media literacy to mean the acquisition of technical skills alone. The Europe2020 strategy, for instance, asserted that citizens would need to grasp media literacy skills to advantage them in the labour market. These technical competencies, what we call digital skills, bring with them easily identifiable commercial benefits for certain industries: this is to be expected, the European Union promotes the Single Market and the elimination of trade barriers.

But that cannot justify the redefinition of media literacy as simply the promotion of online access, shedding the critical aptitudes of being able to evaluate and assess media messages. To do so is to ignore its preeminent social, cultural and political value (in addition to its obvious technical and economic implications).

In our opinion, the Commission’s approach, to disregard any reference to research-based evidence, ran counter to the spirit of the Directive itself.

The actions of the Commission in this matter were justified by claiming that media literacy is a matter of education alone, which would, by happy coincidence, render it the responsibility of national governments. But for the Commission to wash its hands of the matter was to overlook the fact that the competencies associated with media literacy impact upon content access, consumer protection, access and right to information, recognition of media pluralism, and many more. It was the reason that media literacy provisions were included in the Directive in the first instance.

EAVI accepts that it is not the only voice in this conversation. Other groups who petition and lobby the Commission on the matter of media literacy include the media industry itself, who doubtless benefit from consumer base with the technical competency to access the media, but not the critical faculty to demand quality, ethical media content. Could it really be that their power and resources would ensure that the definition of media literacy in the Directive did not inconvenience them?

We at EAVI fought back. As part of the research community3, we argued for years that technology is certainly capable of enriching the lives of citizens, but those competencies should not focus exclusively on technical skills. Media literacy is, in fact, the development of individual critical understanding and citizens’ participation in public life. It is, quite simply, the empowerment and interaction of individuals through the media.

EAVI’s campaign was relentless: we drafted position papers and lobbied MEPs and Committee Members. In June 2016, we organised a debate at the European Parliament, where the next decision on the Directive was to be taken.

The peak of the campaign was the proposal to amend the Directive, which was drafted with the help of many colleagues4, and submitted to Members of the European Parliament in October 2016.

Following from this, some MEPs from across the political spectrum, including the Rapporteur of the AVMSD and the Chairman of the Culture Committee, put forward our amendments. On 25 April 2017, and as a result of our long and tireless campaign, measures to reintroduce media literacy in the AVMSD, in its true form, were adopted by the European Parliament Culture Committee.5

I am glad as ever to observe that the EU legislative process allowed us finally to influence positively the dossier in question. Although EU bureaucracy is often slow, it does give us a real chance to participate, if you know how to navigate the complex environment.

The Directive now includes a comprehensive definition of media literacy. It also asks for Member States to report on practices, policies and accompanying measures they support in the field of media literacy.

Media literacy was nowhere: now it is here!

See the new text adopted by the Culture Committee of the European Parliament

New (8a)

In order to enable citizens to access information, to exercise informed choices, evaluate media contexts, use, critically assess and create media content responsibly, they need advanced media literacy skills. This would allow them to understand the nature of content and services taking advantage of the full range of opportunities offered by communications technologies, so that they can use media effectively and safely. Media literacy should not be limited to learning about tools and technologies, but should aim to equip individuals with the critical thinking skills required to exercise judgement, analyse complex realities, recognise the difference between opinions and facts, and resist all forms of hate speech. The development of media literacy for all citizens, irrespective of age, should be promoted.New art. 33

By[date – no later than four years after adoption] at the latest, and every three years thereafter, the Commission shall submit to the European Parliament, to the Council and to the European Economic and Social Committee a report on the application of this Directive and, if necessary, make further proposals to adapt it to the developments in the field of audiovisual media services, in particular in the light of recent technological developments, the competitiveness of the sector as well as a report on practices, policies and accompanying measures supported by Member States in the field of media literacy.

1. No explicit text references appeared neither among the issues listed to be considered in the review of the AVMSD nor in any subsequent question (with the marginal exception of a mention, in brackets, within the section protection of minors).

2. Difference Day event in Brussels, on 3 May 2017 see www.differenceday.com

3. European-wide studies including by UNESCO, OECD, the Council of Europe, and mainly the European Commission itself, have highlighted the significance of a critical consumption of media content.

4. Including Divina Frau Meigs of UNESCO GAPMIL, Leo Pekkala of the National Audiovisual Institute in Finland, Giovanni Melogli of the Alliance of Journalistes and Maia Cappello of the European Audiovisual Observatory who provided factual information which allowed decision makers to conclude that media literacy should be part of the Directive.

5. Amendements presented by members of the European Parliament Petra Kammerevert, Julie Ward, Silvia Costa, Curzio Maltese, Zdzislaw Krasnodebski, Isabella Adinolfi, Nikolaos Chountis, Martina Michels. The legislative process foresees more steps, and key decisions will be taken by the Plenary of the EP and the Council (the national governments).

EAVI’s secretary general Paolo Celot on EAVI’s campaign resulting in the European Parliament’s vote to re-introduce media literacy to the Audiovisual Media Services Directive.

When the European Commission opened their public consultation on the revision of the Audio Visual Media Services Directive, I had to read it twice. I could not believe that any explicit mention of media literacy was absent from its frame closed format.¹

Were I a cynic, I would have considered the absence suspect. It was almost as though the questions had been drafted in order to pre-ordain the outcome – which was that media literacy was not to feature in the Directive.

My suspicions turned out to be well-founded. When the European Commission presented its proposal in May 2016, media literacy was not mentioned even once.

I couldn’t believe it was possible. We at EAVI have worked with the European Commission for more than a decade. The importance of media literacy was highlighted for years in innumerable studies and policy documents as a critical issue when informing, inter alia, audiovisual policies.

I began to think that it was a dream, when I heard European Commissioner Tibor Navracsics saying, “I can not think of anything better than media literacy”.2

In hindsight, the signals were clear. The Commission had been quietly warping the definition of media literacy to mean the acquisition of technical skills alone. The Europe2020 strategy, for instance, asserted that citizens would need to grasp media literacy skills to advantage them in the labour market. These technical competencies, what we call digital skills, bring with them easily identifiable commercial benefits for certain industries: this is to be expected, the European Union promotes the Single Market and the elimination of trade barriers.

But that cannot justify the redefinition of media literacy as simply the promotion of online access, shedding the critical aptitudes of being able to evaluate and assess media messages. To do so is to ignore its preeminent social, cultural and political value (in addition to its obvious technical and economic implications).

In our opinion, the Commission’s approach, to disregard any reference to research-based evidence, ran counter to the spirit of the Directive itself.

The actions of the Commission in this matter were justified by claiming that media literacy is a matter of education alone, which would, by happy coincidence, render it the responsibility of national governments. But for the Commission to wash its hands of the matter was to overlook the fact that the competencies associated with media literacy impact upon content access, consumer protection, access and right to information, recognition of media pluralism, and many more. It was the reason that media literacy provisions were included in the Directive in the first instance.

EAVI accepts that it is not the only voice in this conversation. Other groups who petition and lobby the Commission on the matter of media literacy include the media industry itself, who doubtless benefit from consumer base with the technical competency to access the media, but not the critical faculty to demand quality, ethical media content. Could it really be that their power and resources would ensure that the definition of media literacy in the Directive did not inconvenience them?

We at EAVI fought back. As part of the research community3, we argued for years that technology is certainly capable of enriching the lives of citizens, but those competencies should not focus exclusively on technical skills. Media literacy is, in fact, the development of individual critical understanding and citizens’ participation in public life. It is, quite simply, the empowerment and interaction of individuals through the media.

EAVI’s campaign was relentless: we drafted position papers and lobbied MEPs and Committee Members. In June 2016, we organised a debate at the European Parliament, where the next decision on the Directive was to be taken.

The peak of the campaign was the proposal to amend the Directive, which was drafted with the help of many colleagues4, and submitted to Members of the European Parliament in October 2016.

Following from this, some MEPs from across the political spectrum, including the Rapporteur of the AVMSD and the Chairman of the Culture Committee, put forward our amendments. On 25 April 2017, and as a result of our long and tireless campaign, measures to reintroduce media literacy in the AVMSD, in its true form, were adopted by the European Parliament Culture Committee.5

I am glad as ever to observe that the EU legislative process allowed us finally to influence positively the dossier in question. Although EU bureaucracy is often slow, it does give us a real chance to participate, if you know how to navigate the complex environment.

The Directive now includes a comprehensive definition of media literacy. It also asks for Member States to report on practices, policies and accompanying measures they support in the field of media literacy.

Media literacy was nowhere: now it is here!

See the new text adopted by the Culture Committee of the European Parliament

New (8a)

In order to enable citizens to access information, to exercise informed choices, evaluate media contexts, use, critically assess and create media content responsibly, they need advanced media literacy skills. This would allow them to understand the nature of content and services taking advantage of the full range of opportunities offered by communications technologies, so that they can use media effectively and safely. Media literacy should not be limited to learning about tools and technologies, but should aim to equip individuals with the critical thinking skills required to exercise judgement, analyse complex realities, recognise the difference between opinions and facts, and resist all forms of hate speech. The development of media literacy for all citizens, irrespective of age, should be promoted.New art. 33

By[date – no later than four years after adoption] at the latest, and every three years thereafter, the Commission shall submit to the European Parliament, to the Council and to the European Economic and Social Committee a report on the application of this Directive and, if necessary, make further proposals to adapt it to the developments in the field of audiovisual media services, in particular in the light of recent technological developments, the competitiveness of the sector as well as a report on practices, policies and accompanying measures supported by Member States in the field of media literacy.

1. No explicit text references appeared neither among the issues listed to be considered in the review of the AVMSD nor in any subsequent question (with the marginal exception of a mention, in brackets, within the section protection of minors).

2. Difference Day event in Brussels, on 3 May 2017 see www.differenceday.com

3. European-wide studies including by UNESCO, OECD, the Council of Europe, and mainly the European Commission itself, have highlighted the significance of a critical consumption of media content.

4. Including Divina Frau Meigs of UNESCO GAPMIL, Leo Pekkala of the National Audiovisual Institute in Finland, Giovanni Melogli of the Alliance of Journalistes and Maia Cappello of the European Audiovisual Observatory who provided factual information which allowed decision makers to conclude that media literacy should be part of the Directive.

5. Amendements presented by members of the European Parliament Petra Kammerevert, Julie Ward, Silvia Costa, Curzio Maltese, Zdzislaw Krasnodebski, Isabella Adinolfi, Nikolaos Chountis, Martina Michels. The legislative process foresees more steps, and key decisions will be taken by the Plenary of the EP and the Council (the national governments).